This post is written by Harry Marks, the mind behind one of my favorite podcasts, Covered. you should check it out Harry’s interview style is excellent.

I was unable to catch California Typewriter, a documentary from Doug Nichol, in theaters during its limited run, so instead I purchased it from iTunes a few days before Thanksgiving. I’m not sure what I expected. Certainly a heavy dose of hipsters nostalgic for an era they never lived so as to set themselves apart from the iPad crowd. However, this movie, unlike others centered around the tools of creators, didn’t give me what I expected and in fact, delivered something more.

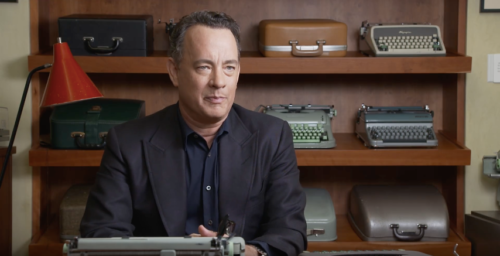

Looking at the poster, with its flaming sheet of paper sticking out the top of a vague, blue 1970s machine, one might think the movie was about the men in the four boxes at the top. Tom Hanks is arguably the most famous typewriter collector in the world, but he doesn’t feature that heavily in the film; John Mayer, David McCullough, and Sam Shepard are far more prominent, perhaps because the typewriter plays a bigger role in their creative endeavors. But these celebrities are not the focus of the film. They are more akin to hype men, expounding on the typewriter’s beauty and longevity while the rest of the movie focuses on its namesake: a tiny shop in Berkley, California that repairs, restores, and resells vintage typewriters.

Looking at the poster, with its flaming sheet of paper sticking out the top of a vague, blue 1970s machine, one might think the movie was about the men in the four boxes at the top. Tom Hanks is arguably the most famous typewriter collector in the world, but he doesn’t feature that heavily in the film; John Mayer, David McCullough, and Sam Shepard are far more prominent, perhaps because the typewriter plays a bigger role in their creative endeavors. But these celebrities are not the focus of the film. They are more akin to hype men, expounding on the typewriter’s beauty and longevity while the rest of the movie focuses on its namesake: a tiny shop in Berkley, California that repairs, restores, and resells vintage typewriters.

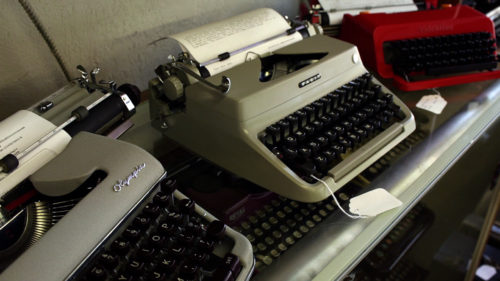

Herb Permillion, the store’s owner, his daughters, and repairman Kenneth Alexander keep things running four days a week. It’s almost enough to validate the “small businesses are the backbone of the American economy” platitude politicians spout right before they vote to tax the hell out of them. I found myself pausing and searching eBay throughout the film because of the way Ken talked about a particular bell sound or how his fingers danced over a machine as though he’d built it himself. This family of do-or-die typewriter aficionados lives and breathes the clicks and clacks of yesteryear and it is impossible to not get swept up in their genuine love for these objects.

Herb Permillion, the store’s owner, his daughters, and repairman Kenneth Alexander keep things running four days a week. It’s almost enough to validate the “small businesses are the backbone of the American economy” platitude politicians spout right before they vote to tax the hell out of them. I found myself pausing and searching eBay throughout the film because of the way Ken talked about a particular bell sound or how his fingers danced over a machine as though he’d built it himself. This family of do-or-die typewriter aficionados lives and breathes the clicks and clacks of yesteryear and it is impossible to not get swept up in their genuine love for these objects. Some might say a documentary about people repairing typewriters wouldn’t be very entertaining (I beg to differ), so when the cameras aren’t inside the shop, they’re pointed at the men and women who collect or make their living from typewriters. When Tom Hanks talks about one of the over 200 typewriters in his collection, it’s like watching Jay Leno discuss a rare car in his garage. You can’t help but smile and feel the warmth of his admiration for them. 1776 author David McCullough writes all his books on an old Royal in his backyard writing shed. Silvi Alcivar is a “poet on demand” who composes short verse on her red Royal Custom III in subway stations and at street fairs.

Some might say a documentary about people repairing typewriters wouldn’t be very entertaining (I beg to differ), so when the cameras aren’t inside the shop, they’re pointed at the men and women who collect or make their living from typewriters. When Tom Hanks talks about one of the over 200 typewriters in his collection, it’s like watching Jay Leno discuss a rare car in his garage. You can’t help but smile and feel the warmth of his admiration for them. 1776 author David McCullough writes all his books on an old Royal in his backyard writing shed. Silvi Alcivar is a “poet on demand” who composes short verse on her red Royal Custom III in subway stations and at street fairs. Not all featured are writers and poets, though. Jeremy Mayer creates amazing sculptures of animals and humans out of old typewriter parts. I couldn’t help but cringe at his prying apart old Selectrics and Coronas to construct fingers and cheek bones for his skeletal people. When a film is dedicated to the preservation of such beautiful machines, seeing someone mangle them to feed their Frankenstein-like need to create feels like watching a person make wallpaper from torn-out Bible pages. Mayer’s work is fascinating in a macabre kind of way.

Not all featured are writers and poets, though. Jeremy Mayer creates amazing sculptures of animals and humans out of old typewriter parts. I couldn’t help but cringe at his prying apart old Selectrics and Coronas to construct fingers and cheek bones for his skeletal people. When a film is dedicated to the preservation of such beautiful machines, seeing someone mangle them to feed their Frankenstein-like need to create feels like watching a person make wallpaper from torn-out Bible pages. Mayer’s work is fascinating in a macabre kind of way.

Regardless of how each individual uses (or abuses) typewriters, every single person in California Typewriter has a different and unique reason for why he or she enjoys them, be it the sound, or the joy of an analog lifestyle, or the satisfaction of putting actual words on an actual page. This is what’s most inspiring about the documentary: everyone in it is different, just like every typewriter is different. The bells chime in different tones. An Olympia has a crispier “chunk” than a Smith-Corona. Keys are spaced and shaped differently, and each of those characteristics is something to either entice or repel a potential owner. One person makes sculptures with parts while another makes music. One types non-fiction in a shed while another types poetry in public. The typewriter can be a symphony and a work of art, and while different people may use it in different ways, its purpose is clear: to create.

Regardless of how each individual uses (or abuses) typewriters, every single person in California Typewriter has a different and unique reason for why he or she enjoys them, be it the sound, or the joy of an analog lifestyle, or the satisfaction of putting actual words on an actual page. This is what’s most inspiring about the documentary: everyone in it is different, just like every typewriter is different. The bells chime in different tones. An Olympia has a crispier “chunk” than a Smith-Corona. Keys are spaced and shaped differently, and each of those characteristics is something to either entice or repel a potential owner. One person makes sculptures with parts while another makes music. One types non-fiction in a shed while another types poetry in public. The typewriter can be a symphony and a work of art, and while different people may use it in different ways, its purpose is clear: to create. After watching the film, I felt compelled to drop a fresh sheet of paper into my own Smith-Corona and start a new short story. My words hit the page like gunfire. Sure, it was nice to slow down and get away from the notifications and dings of new email, but more than that it was fun. Typewriters are fun. Typing on a typewriter is fun. Fun is something not talked about when writing on a computer or even by hand. One is mundane, the other a chore (I’m failing NaNoWriMo by hand and it is less than amusing). The people of California Typewriter, both the shop and the film, embrace the fun side of the tools we take for granted. Their enjoyment is almost better than the footage of all the beautiful typewriters they surround themselves with. Almost.

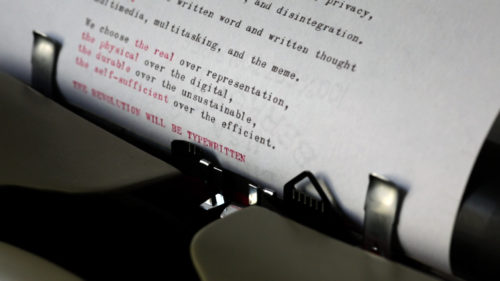

After watching the film, I felt compelled to drop a fresh sheet of paper into my own Smith-Corona and start a new short story. My words hit the page like gunfire. Sure, it was nice to slow down and get away from the notifications and dings of new email, but more than that it was fun. Typewriters are fun. Typing on a typewriter is fun. Fun is something not talked about when writing on a computer or even by hand. One is mundane, the other a chore (I’m failing NaNoWriMo by hand and it is less than amusing). The people of California Typewriter, both the shop and the film, embrace the fun side of the tools we take for granted. Their enjoyment is almost better than the footage of all the beautiful typewriters they surround themselves with. Almost. For me, California Typewriter has the potential to be the On Writing of movies, a well to revisit and quench one’s thirst when the words run dry. One viewing and I had already slipped a sheet of paper through the platen. No operating systems to update, no Internet required, no interruptions, just me and the words. You may call us hipsters or contrarians. You may look down on our love of the old ways, but our machines are 60, 70, 80 years old or more. They have lasted through numerous presidents, World Wars, the dot com bubble, and they may even outlast us.

For me, California Typewriter has the potential to be the On Writing of movies, a well to revisit and quench one’s thirst when the words run dry. One viewing and I had already slipped a sheet of paper through the platen. No operating systems to update, no Internet required, no interruptions, just me and the words. You may call us hipsters or contrarians. You may look down on our love of the old ways, but our machines are 60, 70, 80 years old or more. They have lasted through numerous presidents, World Wars, the dot com bubble, and they may even outlast us.

California Typewriter avoids the common traps found in similar documentaries. It is more than a celebration of an enduring creative tool. It is proof that obsolescence is not inevitable, but a suggestion as long as these machines can enchant new audiences and skillful hands continue to keep them running. We’ve embraced analog because despite the time it takes to complete a task, it is more satisfying. Tactile. Personal. I cannot think of a better representation of these principles than California Typewriter.

California Typewriter is available now for rent or purchase on iTunes.

Harry Marks is the host of the literary podcast COVERED where he interviews authors about their books and the writing process. His fiction can be read at HelloHorror and in Plumbago Magazine.